Insights

Unlocking recyclability – Addressing gaps beyond Design for Recycling (DfR)

As the cosmetics industry accelerates toward circularity, driven by regulatory push in Europe and worldwide, Design for Recycling (DfR) has emerged as a cornerstone of packaging innovation. Over the past years, SPICE members have worked collectively, improving cosmetics packaging recyclability by removing disruptive components, favoring mono-materials, and aligning with evolving regulatory expectations, such as the EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation(A). However, DfR alone does not guarantee actual at scale recyclability in 2035, as it needs to be complemented by well-equipped and designed collection and sorting infrastructures, whose implementation depends also on regional dedicated authorities.

Cosmetic packaging(1), representing a relatively small contributor to total waste tonnage, particularly small format(2) and rigid rolling formats, continues to face significant challenges in sorting or recovery infrastructures even if some countries have already taken initiatives. Real world recycling outcomes remain limited due to fragmented and inconsistent collection and sorting infrastructures globally. Sorting infrastructures, in particular, often still separate items close to 50 mm in size through trommel separators, depending on the country(B)(C). While this Insight focuses on cosmetics, small-format packaging is also a challenge across food, beverage, and healthcare sectors, where similarly sized items often fail to be sorted or recovered. Beyond their small size and rigid & rolling format, cosmetic packaging often features complex shapes and decorative elements that further complicate mechanical sorting and material recovery.

It is also important to note that European standards for DfR, developed by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) under mandate from the European Commission, do not quite righty consider the size, mass, or shape of packaging as criteria for recyclability. This prevents incentives to increase pack sizes simply to qualify as recyclable. Instead, the focus shall be given to expanding collection schemes and ensuring sorting technologies can process all relevant formats, including small, rigid, and rolling cosmetic packaging items, so that recyclability assessments align with real-world recovery potential(D).

SPICE recommends collective industry action to harmonize these essential practices, ensuring packaging designed for recyclability truly achieves its potential, thus accelerating the industry’s shift toward genuine sustainability and circularity.

Recyclability Starts with Collection

Today, in many countries, cosmetic formats designed with best-in-class recyclability principles are still being discarded as non-recyclable waste(E). Often, the barrier is not the component itself but the fragmented and inconsistent infrastructure it enters, after the collection step.

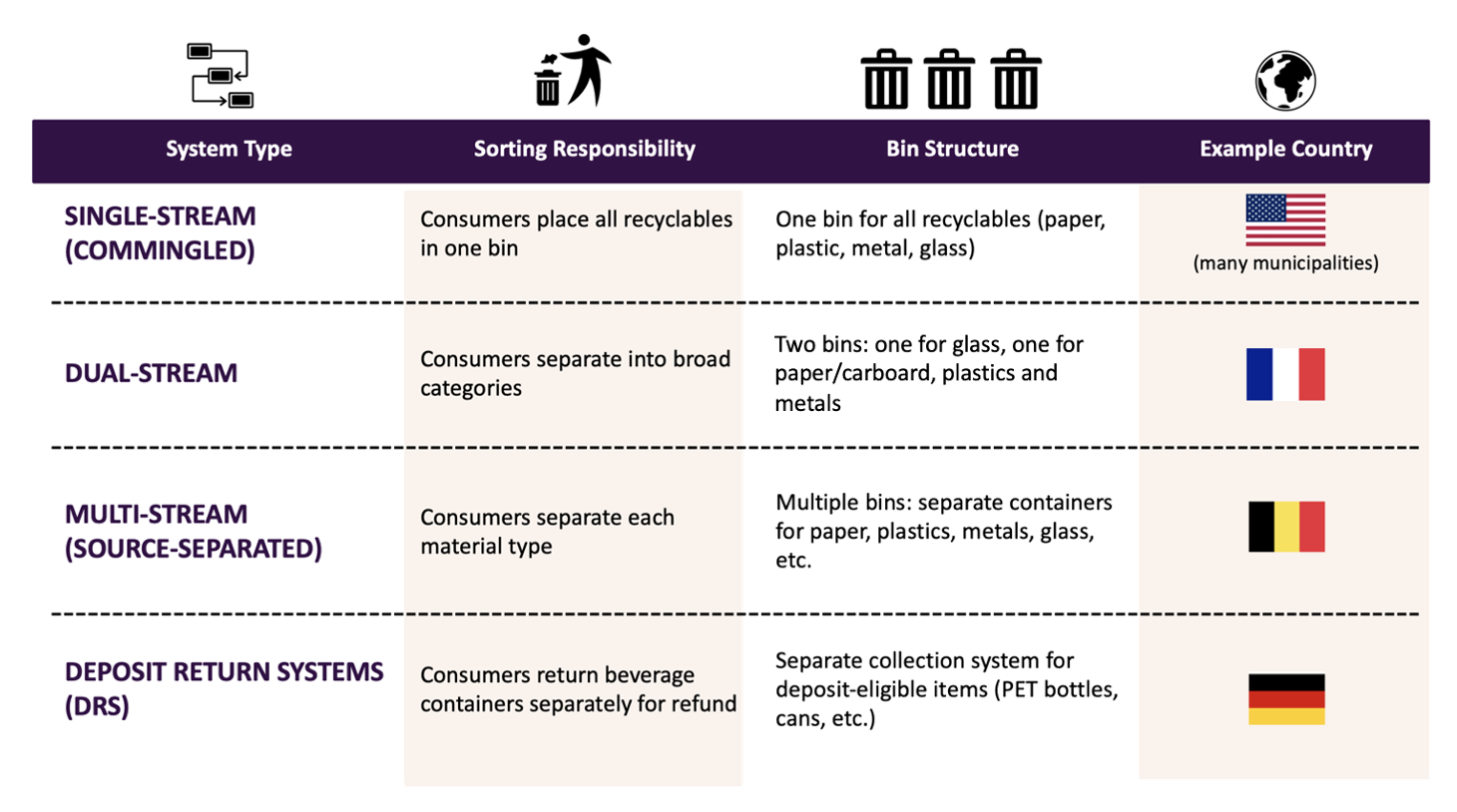

Recyclables can be collected through various systems (Figure 1), each with distinct impacts on material quality and Material Recovery Facilities (MRF) operations, as shown in the next paragraph.

Figure 1: Overview of recycling collection system setups and example countries.

At the same time, Extended Producer Responsibilities (EPR)(3) schemes, are rapidly being phased in beyond Europe, often creating a disconnect between what can be realistically achieved with the infrastructure in place and the required levels of components’ recovery and recycling, especially for the cosmetics industry.

For example, in the US, California is leading the way with an EPR scheme for single use packaging, whose introduction has been discussed since the release of Senate Bill 54 back in 2022(E). However, the state’s curbside collection scheme is still single-stream, causing glass and plastics to be collected together and high value and/or volume components such as PET bottles to be prioritized during sorting at MRFs. On the other hand, small-format packaging, including many cosmetic and personal care products, tend to literally fall through the machinery, ending up with broken glass or other fine residue(F). Moreover, California’s Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO), Circular Action Alliance (CAA), works with a list of Covered Material, published as required by California Senate Bill 54, indicating what is recyclable or not. As such, all plastic flexible and film packaging (e.g., pouches, sachets, wraps) and “plastic small” formats (items with two or more sides ≤ 2 inches, such as cosmetic samples or small containers) are not designated as recyclable(G).

Collection – Sorting Interdependence: Impact on Cosmetic Packaging Fate

The way recyclables are collected upstream fundamentally determines how a MRF must be designed and operated downstream.

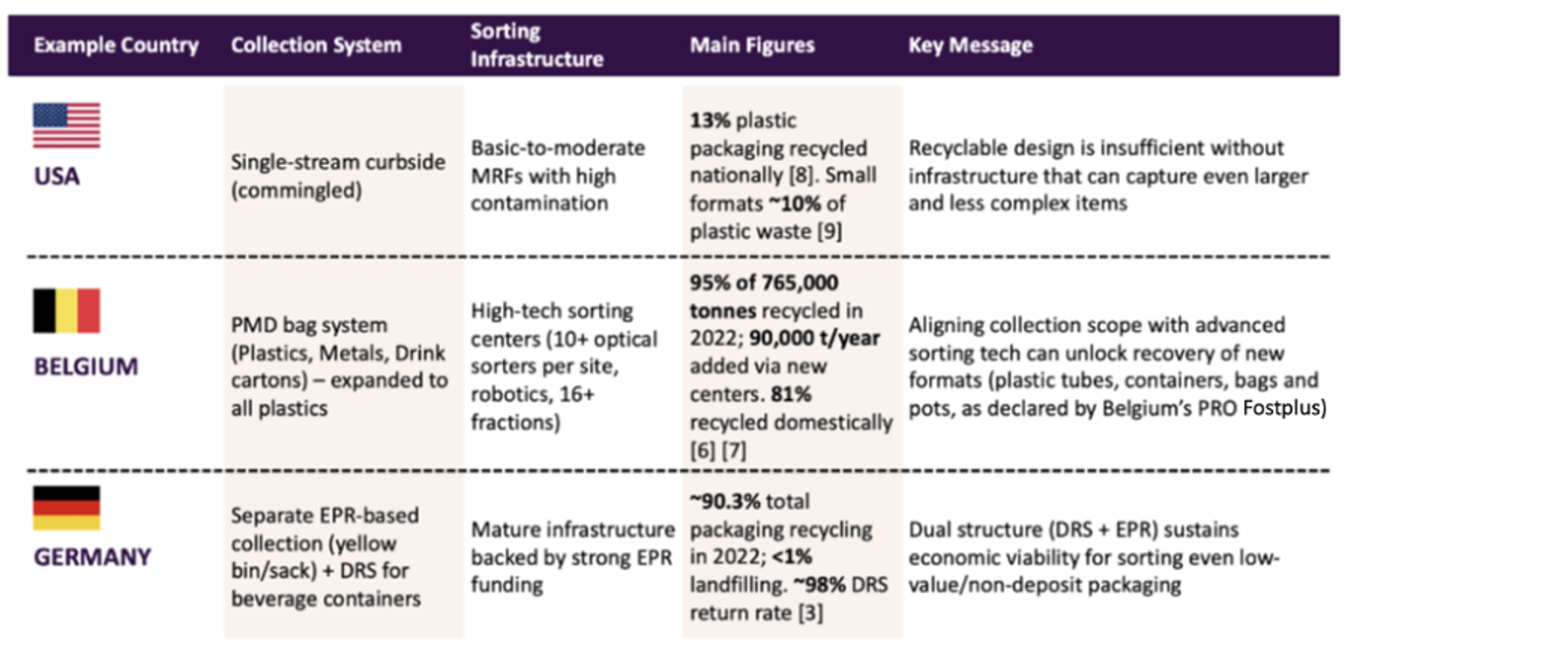

Countries like Germany, on the other hand, introduced a Deposit Return System for PET bottles, glass bottles, and metal cans(H). As a result, sorting facilities can concentrate on the remaining packaging (like food and cosmetic packaging, trays, tubs, films, etc.), but it also means they forego the revenue that those valuable bottle materials might have brought(I). In Germany, this issue is mitigated by the EPR structure: producers finance the Dual System, so the economics of the MRFs are supported by packaging fees, ensuring even non-deposit packaging (including many cosmetic containers) are still worth sorting and recycling(J). While DRS systems are well-established for beverage containers, they are not proposed here for cosmetics packaging but serve to illustrate how targeted systems can enable broader recovery efficiencies.

Finally, the specific case of Belgium demonstrates how aligning collection scope with advanced sorting technology can dramatically boost packaging recovery, even for formats previously considered hard to recycle, such as films, tubes, and small rigid plastics. The country expanded its PMD (Plastics, Metals, and Drink cartons) collection stream, once limited mostly to plastic bottles and larger containers, to include all plastic packaging. Coupled with investments in five high-tech sorting centers, this added capacity for 90,000 tonnes of additional packaging annually. In 2022, 95% of the ~765,000 tonnes of household packaging placed on the market was recycled, 81% of it within Belgium, making it one of the highest capture rates in Europe(K)(L). Although, Belgium’s PRO Fostplus declares that plastic tubes and containers, bags and pots, are now recovered and recycled, the potential of these new state-of the art centers to achieve the same result for small cosmetics packaging is unclear.

Figure 2 summarizes the examples discussed above, highlighting key figures and takeaways that illustrate how collection and sorting systems impact real-world recyclability of cosmetic packaging:

Figure 2: How aligning collection systems with sorting infrastructure impacts packaging recovery outcomes across different countries

Conclusion

This Insight highlights a clear reality: real recyclability at scale, particularly for small cosmetics items, can be achieved only with a mature sorting infrastructure and adequate collections systems. If these prerequisites are not met, efforts to achieve DfR compliance for items such as cream jars, lipsticks and tubes, may not ultimately matter.

To move from ambition to outcome, SPICE calls for collective action between cosmetics packaging producers, sorting centres operators and authorities responsible for collection systems, to all share responsibility when it comes to complex-to-sort waste. This ideally means expanding collection schemes to capture all relevant packaging formats, including small, rigid and rolling cosmetic items. This require a certain level of innovation for collection, detection and ejection processes to ensure sorting technologies are equipped to process that waste. Still, cosmetics packaging likely represents only a small portion of total packaging waste. While precise, up-to-date figures are limited, a 2017 global estimate suggested that small-format plastic packaging, including sachets, lids, and cosmetic samples, accounts for roughly 10% of the plastic packaging market by weight and up to 50% by number of items(M). Hence, guidance on collection, sorting and design must be aligned with the broader realities of multi-sector packaging flows.

Recyclability priorities must also reflect local consumption patterns, as packaging formats vary widely across countries. Moreover, some cosmetics items have a higher chance of being discarded in a single stream bin, such as the ones still commonly placed in the bathrooms, showing that consumer engagement is another area of required intervention.

Improving recyclability at scale requires shared responsibility. While brand owners can continue efforts towards 100% Design for Recycling, format simplification, and recyclability guidance, many critical factors, such as collection system coverage and equipment specifications like trommel screen sizes, lie in the hands of policymakers, member’s states, Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs)(4) and infrastructure operators.

SPICE and its members are committed to taking action, by designing for real-world recyclability, promoting the development of supportive collection systems, and aligning technical guidance with sorting realities. At the same time, collaboration with policymakers, PROs and infrastructure partners is essential to deliver impact at scale.

With a clear understanding of the challenges facing cosmetic packaging, the SPICE initiative is taking proactive steps to advance industry alignment on circular design. Building on its expertise, SPICE is preparing a comprehensive analysis of the forthcoming standards on design for recycling and recyclability, assessing how it aligns with — and where it diverges from — existing design-for-recyclability guidelines and real-world recyclability at scale. In parallel, SPICE and its members will work collaboratively to map and categorize these potential gaps, highlighting practical pathways to close them wherever viable solutions exist – including packaging design, collection, sorting and recycling. Where technical, functional, timing, or cost constraints make solutions unfeasible, SPICE will transparently identify these barriers, helping to inform and work with both industry and policy makers.

Definitions

(1) This Insight focuses specifically on household packaging waste, where cosmetic products such as cream jars, make-up items (e.g. lipsticks) and tubes are primarily disposed.

(2) For the purpose of this article, small-format items are defined as items below 50 mm in 2 dimensions (2 inches) – as per the Association for Plastics Recyclers (APR), although even larger small items can be lost (5).

(3) A policy approach that makes producers responsible for financing or managing the collection, sorting, and recycling of their packaging after use.

(4) An entity set up to manage packaging waste obligations on behalf of producers, often overseeing collection, sorting, and recycling under EPR schemes.

Sources

(A) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2025/40/oj/eng

(B) https://www.iekrw.de/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2025_02-04-Stoffstromtrennung-Restabfall-4.pdf

(C) https://apps.dnr.wi.gov/doclink/waext/wa1835.pdf

(D) https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/4f92e1b9-0e0c-4b85-987d-045c83ccd6ce/en-13430-2004

(E) https://www.closedlooppartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Updated-Final_Small-Plastics-Recovery-Report_2025.pdf

(F) https://calrecycle.ca.gov/packaging/packaging-epr/

(G) https://www2.calrecycle.ca.gov/Docs/Web/129525

(H) https://www.tomra.com/reverse-vending/media-center/feature-articles/germany-deposit-return-scheme#:~:text=Germany%20has%20the%20world%E2%80%99s%20largest,dense%20network%20of%20return%20locations

(I) https://www.recyclingtoday.com/news/mit-researchers-national-bottle-bill-could-increase-pet-bottle-recovery/#:~:text=The%20study%20found%20it%20is,materials%20in%20the%20recycling%20stream

(J) https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/12/deposit-refund-systems-and-the-interplay-with-additional-mandatory-extended-producer-responsibility-policies_c92a063b/a80f4b26-en.pdf

(K) https://www.fostplus.be/en/blog/fost-plus-recycled-95-of-all-household-packaging-in-2022#:~:text=By%20expanding%20the%20contents%20to,in%202022

(L) https://www.fostplus.be/en/blog/last-sorting-centre-opens-its-doors#:~:text=with%20PMD,quality%20materials%20to%20the%20recycling

(M) https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_NEWPLASTICSECONOMY_2017.pdf

SPICE TOOL RECYCLABILITY APPENDIX

This document is aimed to support SPICE Tool users in the assessment of their packaging environmental footprint, and more specifically on distinct packaging components’ recyclability.

Access the appendix

SPICE TOOL RECYCLED CONTENT APPENDIX

This document is aimed to support SPICE Tool users when assessing post-consumer recycled content by clarifying the definition of post-consumer and pre-consumer material according to the ISO 14021 and through specific examples.

Access the appendix